The UNHCR reports that a staggering 5.9 million refugees have fled Ukraine, with 3.2 million arriving in Poland alone. These numbers dwarf arrivals from Europe’s last (so-called) 'refugee crisis' in 2015. Back then, Europe reacted to people arriving from Syria, Afghanistan, Eritrea, Somalia and Iraq by tightening legislation and restricting rights. This time we are told these refugees ‘look like us’, are ‘civilised’, ‘live in a democracy’ and are ‘middle class’.

And we see unprecedented action. Within only eight days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU unanimously adopted legislation ensuring refugees can access public services, housing and labour markets. This swift response marks a dramatic shift from the hostile environment that has taken hold in Europe in recent years.

Contrary to contemporary political narratives, this distinction between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ refugees is increasingly out-of-step with the majority of the European public. What’s more, cities are leading the way by pioneering a more compassionate and practical response, which national governments would do well to follow.

A refugee hierarchy

While many of us would like to herald this change in policy as the end of ‘Fortress Europe’, it seems we are instead witnessing the ‘refugee hierarchy’.

This racialised hierarchy was evident at the outset of the war when we first saw Africans stopped at the Ukrainian border, with our ODI colleagues stating at the time ‘they are simply considered less worthy’. Ukrainian refugees are being welcomed into Polish homes and schools. And some Ukrainian children will be able to complete their school year, in their own language, in schools newly set up for displaced children. Contrast this to Poland’s relatively recent experience at its border with Belarus only last year. Thousands of refugees from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraqi Kurdistan were violently pushed back and abandoned without food or medical aid in freezing conditions.

Few will realise this crisis is still ongoing. Whilst Ukrainians reach sanctuary in Poland, Middle Eastern refugees on the Belarusian border face the option of crossing into war-torn Ukraine or being beaten back by Polish guards.

Of course, such actions are not just occurring in Poland. Refugees attempting to enter southern Europe are regularly branded a threat by politicians and pushed back, illegally, into the Mediterranean with often dire consequences.

Public opinion is far ahead of European governments’ refugee policies

The UK and European public are incredibly welcoming towards Ukrainian refugees. This support is also not a far cry from shared attitudes regarding all refugees, no matter their country of origin.

Our research shows a clear trend of increasingly positive attitudes surrounding immigration in recent years, and reduction in the importance of immigration as a key public issue from 2016 onwards.

And it is clear that over the past decade, European governments’ immigration and asylum policies — which have become increasingly alarming with greater criminalisation and detention of migrants in ‘prison-like conditions’ — have grown ever further away from public attitudes.

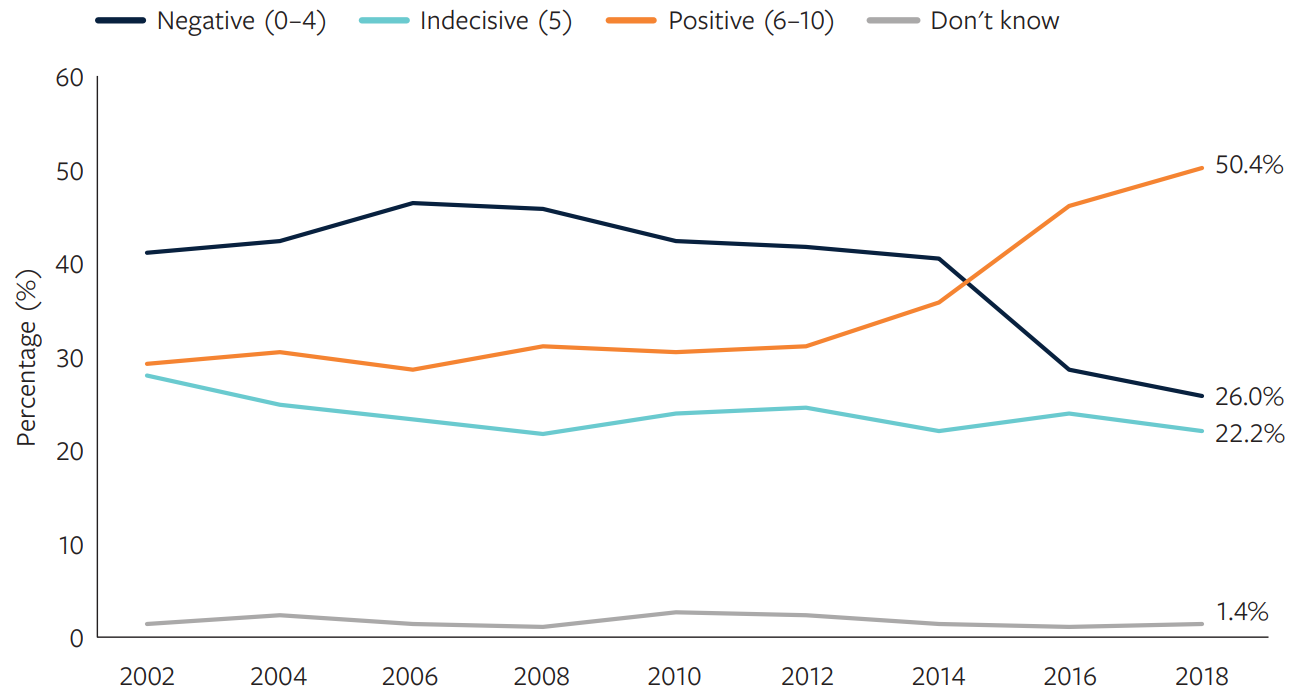

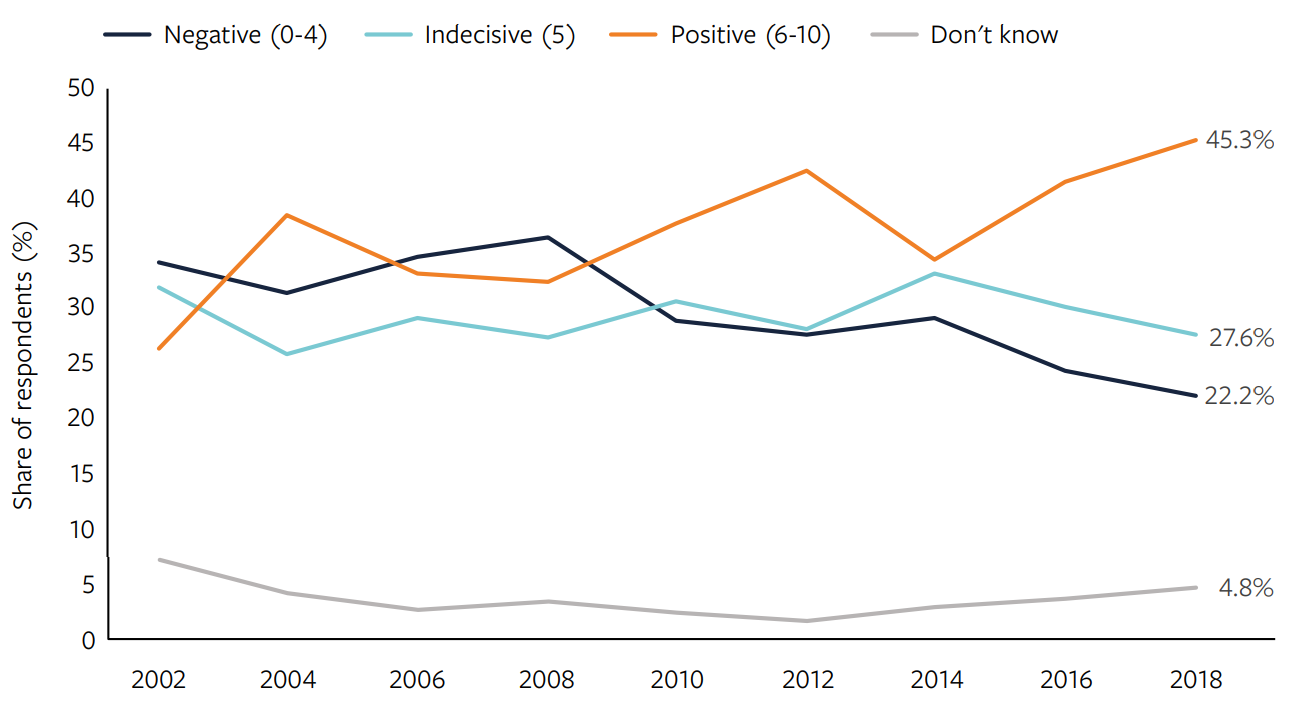

In countries like Sweden attitudes towards immigration have been overwhelmingly positive for decades. In Spain negative attitudes have been in consistent decline since 2008. And even in a country like the UK, long-known for its polarised narratives, attitudes have shifted significantly in recent years. Similar trends have also taken place in France, with positive attitudes exceeding negative ones for the first time in 2018.

UK attitudes towards immigration: does immigration make the UK a worse or better place to live?

Spain attitudes towards immigration: does immigration make Spain a worse or better place to live?

Not only are overall attitudes towards immigration often positive, the European public also express high degrees of sympathy with refugees. In countries such as Germany, there has been consistently strong public support for refugee protection. And in the UK an increasingly large share of the public believe the country should allow people fleeing persecution or war to come and live in Britain; polling from April 2022 shows that only 5% of the public believe the UK should not accept refugees and only 10% believe the country should accept lower numbers of refugees.

European cities are now on the frontline of the refugee response

Cities are opening their doors to Ukrainian citizens, and leading resettlement efforts.

In Warsaw, the city population has increased by 17% in one month. There has been an outpouring of support for refugees arriving in the city. Residents, civic organisations and businesses have provided food, medical aid, shelter and educational support, with Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski calling for financial support from the Polish government and the international community.

The solidarity offered by cities extends beyond Eastern Europe. In Italy, the mayors of Milan and Bologna have taken a lead role in delivering health services and offering shelter (in Italian) to Ukrainian people. In the same vein — the city of Bristol has quickly set up a resettlement programme for Ukrainian refugees offering shelter, education and health support.

Local governments, more in sync with public attitudes?

There is broad evidence beyond Ukraine that European mayors are increasingly challenging negative narratives on migration. French cities are a clear example. Mayors from Grenoble, Marseille, Lyon, Strasbourg (in French) and Lille, made highly vocal welcomes to those fleeing Afghanistan. The Mayor of Grenoble, one of many French mayors, has also consistently spoken out in favour of reform of France’s immigration policies.

Similarly, while the UK government has maintained its commitment to the hostile environment (alongside an underwhelming response towards Afghan refugees), Bristol’s mayor Marvin Rees launched a resettlement programme and called on private landlords to offer rented accommodation to house Afghan families, while calling for more central government resources to expand support.

In Spain in 2018 the Mayor of Valencia welcomed 630 migrants in boats that had been turned away from the ports of Malta and Italy. Mayor Ada Colau has also declared Barcelona a city of refuge and developed innovative policies to support refugee integration, in strong opposition to right-wing pressure to harshen Spanish immigration policy.

These examples show cities’ history of recognising the dynamic benefits of human mobility and promoting their own inclusive agendas. Their stance is often directly at odds with negative political narratives and the restrictive policies of national governments. Today, cities’ agendas more accurately reflect the reality of people’s attitudes when it comes to how we should respond to those fleeing persecution and conflict. This was true before Ukraine and remains visible as Europe navigates its response to yet another conflict.

It’s time national governments listened to their citizens and urgently provide more safe and legal routes for all refugees. And following cities' examples, they should adopt a more compassionate approach to refugee protection and integration.